THE SECRET

The Limpopo villagers who are living past 100

By Bernadette Wicks

The Vhembe district municipality is home to more people over the age of 100 than anywhere else in the country. Almost half of them live in the Thulamela local municipality, where the proportion who reach this milestone rivals that in Japan's famed "Blue Zone" of Okinawa, according to the latest census data.

Tshisaphungo Maria Ndzeru sits on her stoep in the Ha Vhangani village, bordering a swathe of wild veld in the northern-most reaches of South Africa, waiting for the sound of small hands unlatching the chain-link gate.

It's just gone 14:00 and the children will be returning from school soon.

She is blind, and the soft clink of metal on metal lets her know they are home.

Murendeni Nnzeru runs over, peeling herself free of her backpack, and gets down beside Ndzeru. They have the same broad smile. But there are 89 years between them. Murendeni is 12 and Ndzeru, her great-grandmother, is 101.

According to the 2022 census, there are 1 226 centenarians in the Vhembe district municipality. That's more than anywhere else in the country. And almost half of them - 503 - live here, in the Thulamela local municipality, or, traditionally, Venda.

The modern political history of the region is fraught. It was annexed by the Transvaal government in 1898 and designated a “homeland” and then given “independent republic” status under apartheid.

It is the traditional heartland of the Venda people, whose ancestors first settled here centuries ago. An enclave of dramatic dips and peaks, cloaked in a lush, green mantle, Venda means “pleasant place”.

Blue Zones

Explorer and researcher Dan Buettner coined the term “Blue Zones”, in reference to five regions around the world where, as the official website explains, people enjoy “extraordinary longevity and vitality”.

One of the ways this is measured is by the proportion of people who live to the age of 100.

In Okinawa, Japan, perhaps the best-known official Blue Zone, the figure most often quoted is that around 68 in every 100 000 people reach this milestone.

The latest census data puts it at 87 in every 100 000 in Thulamela, begging the question: could this be South Africa's very own “Blue Zone”?

Fresh chicken

A feisty woman with a stubborn streak according to those who know her, Ndzeru still likes to do things like washing and dressing in the morning herself. But she has a carer, Takalani Tshilongo, who helps her with other daily tasks like boiling water on the fire and dishing up at mealtimes.

Ndzeru's youngest daughter, 54-year-old Molly Nnzeru, also moved back to her childhood home to assist last year, along with Murendeni as well as her two brothers. They are Molly's grandchildren.

“Other people can't take care of my mother like I can,” Molly says.

Almost every other house on the street is home to more members of the family. They drift in and out throughout the day for something to eat or just a catch-up.

Ndzeru's brother-in-law, Madala Joas Ndzeru, is over for lunch today.

“There are those who tell themselves 'I'm old I can't do anything'. But me, I don't allow those things to happen to me,” the 82-year-old Madala says, from across the cloud of steam wafting up from the pots in the centre of the table.

It's fresh chicken and vhuswa ha mutuku (a sour pap) today – Ndzeru's favourite.

She stresses, though, that the chicken must be fresh.

Molly feigns an exasperated sigh.

“I buy every day,” she chuckles.

When she was a younger woman, Ndzeru would often traverse the neighbouring villages on foot. Now that she cannot see or walk far unaided, she prefers friends and family to come to her. She has lived in the same home for 73 years and takes comfort in the familiarity.

The only answer Ndzeru has for what keeps her going is God.

"God loves me."

She regularly attended the Assemblies of God church before losing her eyesight, and the room falls silent as she begins to hum one of her favourite hymns. Its words translate to:

“When I arrive in heaven, what am I going to do? What am I going to see? The name of Jesus, I will glorify His holy name.”

Divine will

Tshikhakhisa Mamashia Magoro, 105; Mmbengeni William Mbedzi, 104; and Nyawasedza Nematomboni, 100, too, believe their longevity is divine will.

Magoro lives in Doli, half an hour away from Ha Vhangani, with her daughter, Lydia Mudau. The house is modest and the garden, vast. Mudau - who at 68 years old herself, still loves nothing more than a game of soccer - grabs a long, knotted stick and shakes down an armful of oranges from a tree heaving with fruit, just steps from the front door. They hit the ground sending a sharp, sweet zing of citrus up and into the air.

A canvas print of a painting of Jesus the Good Shepherd, hung slightly off centre, enjoys pride of place on an otherwise bare wall in the living room.

In a bedroom to the left, Magoro is basking in a shaft of warm mid-morning sunlight. She pulls away a soft blanket draped over her shoulders, to reveal a silver Zion Christian Church (ZCC) star carefully pinned to her dress.

“It's God that has made me live this long,” she says.

Magoro also lost her eyesight several years ago - she doesn't remember how many - and is happiest at home now.

She listens to the radio and enjoys visits from her relatives - especially her grandchildren - who live in the neighbouring villages.

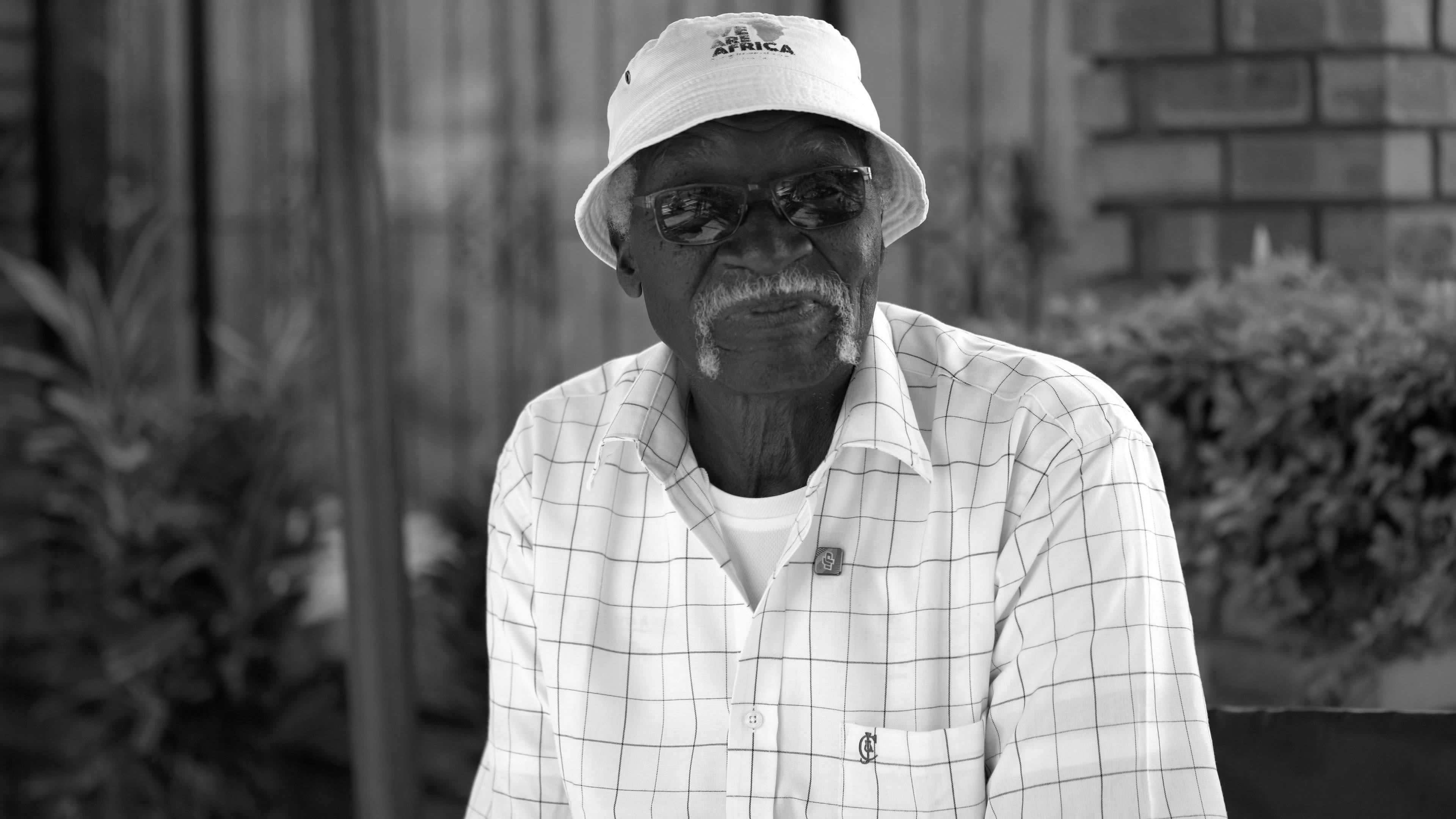

Mbedzi has a wry sense of humour and an infectious laugh.

He worked with big machines on local farms in his younger years, he says.

“Back in the day, I used to dance hard to traditional songs and drink,” he recalls.

“But I don't drink anymore,” he adds quickly.

Mbedzi lived on his own until he was 90, when his 38-year-old “granddaughter”, Azwitamisi Mufamadi, moved in with him.

“She calls me grandfather because I am her mother's uncle,” he explains.

What does he think is behind his long life?

He thinks for a moment and then shrugs,

“Maybe it's God.”

Nyawasedza Nematomboni turned 100 in June.

“I cannot really explain it, it can only be God. God wanted me to live this long,” she says.

She had six children, three of whom she also buried. She sometimes wonders if her long life is not a balancing of the scales.

The first thing she does in the morning is get moving.

“I wake up and walk around,” she says.

She also eats a lot of vegetables and not much meat, and enjoys sleepovers with her great-grandchildren.

Her face softens,

“We chat the whole night.”

Buettner and his team have identified specific “lifestyle habits” which are part of the way of life in almost all official Blue Zones, though, and many of them can be seen here too.

Dubbed the “Power 9”, they include:

● Moving naturally;

● Having a sense of purpose;

● Having routines for destressing;

● Not overeating;

● Eating a diet rich in plant-based foods;

● Drinking alcohol in moderation;

● Belonging to a faith-based community;

● Prioritising family; and

● Moving in social circles that “support healthy behaviours”.

The house of the soul

Chief Livhuwani Matsila is the traditional leader of the Matsila people and says organic, indigenous foods have always been the preference in Venda,

“Our forefathers had a lot of cattle and other animals. But meat was not something that you would eat as often as we do nowadays. It was consumed on special occasions. It would mainly be vegetables and some indigenous chicken.”

He also says physical activity - and trekking the paths carved into the rugged terrain by their generations and generations of livestock - is historically, part of the lifestyle,

“I used to walk in a radius of 50 kilometres looking for cattle, donkeys and goats, it was not a problem.”

Renowned local African traditional health practitioner Dr Mashudu Dima describes the body as “the house of the soul”.

“The soul needs a place where it's clean,” he says.

Dima is widely recognised for his work in indigenous healing and preserving indigenous knowledge and a three-time winner of the National Heritage Council's National Treasure award.

At 88-years-old, he still starts his day at 03:30 every morning, just as he has done since he was a boy. It is the right time, he says, to commune with the ancestors. He still tends to his garden and sees his patients.

“You couldn't run with me,” he says confidently. “We are not carnivorous like lions or leopards who are always looking for meat,” Dima explains.

It is about balance, he says,

"[If] today you have eaten meat, tomorrow you have to have wild vegetables.”

With its fertile soil and warm, wet subtropical climate, the region is home to a variety of different fruits and vegetables.

The roads are lined with stalls manned by smiling women, their shelves piled high with plump bananas and sweet potatoes of every colour – from off white, to bright orange, to deep purple.

In the summer there are litchis and mangoes, with Limpopo the country's largest producer of the latter.

There's a cluster of pawpaw trees on every corner and bushels of spinach and cabbage growing in every garden.

Dima also says indigenous fruits - such as monkey oranges, waterberries, sour plums and baobab fruit - help stave off colds and flu, adding that these types of illnesses are far less common here than in the city.

He further points to the inclusion of insect proteins - such as the region's famed mopane “crunches” (the most accurate term, he says) and its perhaps lesser-known “ginger beetles” - in their traditional diet.

“They are very ginger. Once you chow just two or three, it can be more than 12 hours before your tongue brings back the taste of food,” Dima says, with a knowing smile. He has made this mistake before.

He recommends eating “light” during the day - adding pap should only be eaten at night, before bed - and says alcohol is enjoyed in moderation, with their go-to “wash down" after a meal, mageu.

Dr Mushaphi Lindelani Fhumudzani, who heads up the University of Venda's (UNIVEN's) Department of Nutrition, describes the traditional diet as largely plant-based and made up of vegetables and legumes - such as beans and nuts - as well as insect proteins.

These foods, she continues, are rich in different nutrients, “yet low in fat, and high in fibre, which is good for digestion”.

“So I think all those things, when you look at it, contribute to people living longer,” Fhumudzani explains.

“They end up at lower risk of developing diseases of lifestyle - non-communicable diseases such as [being] overweight, diabetes, hypertension.”

The secret

Nature provides more than physical nourishment for the people of Venda, though, says Dima,

“If you have a problem or stress at home, you can go outside to the bush and meditate… Go outside to the bush and sit down and balance yourself with the stem of a big tree and bow down and listen to the insects, to the wild animals, to the birds, right in the jungle or forest. If you can spend five days in the jungle or forest you can be healed mostly without medicine.”

This, he says, is their “secret”.

They even have their own “spa”, he jokes.

He's referring to their practice of “steaming” - inhaling vapours of indigenous leaves in the winter months - which he says rids their bodies of excess salt.

Kinship and a sense of community is also a fundamental tenet of Venda culture.

Professor Angelina Maphula is a clinical psychologist and associate professor in the Faculty of Health Science at UNIVEN.

"In Venda culture, we believe in a communal concept and that communal concept hosts parents, grandparents and great-grandparents," she says,

"We've been socialised to really take care of our own".

Adds Maphula, regular social engagements and close relationships foster "a sense of purpose" and enhance mental health. This, in turn, "translates to wellness in a holistic manner.

"When someone's mental health is good, we see their well-being thrive in other areas," she says

Says Matsila:

“In town, you don't talk to your neighbour. Even if you are stressed, you can't sit under a tree and talk to a neighbour and say: I have this problem with a child or the husband… You just suffer alone. Here, there's a lot of solidarity in the system. The cultural system's based on solidarity and helping one another.”

He points to stokvels and social clubs “where people gather from time to time and help each other through life issues”.

Church is also, clearly, a big part of life here.

“That whole attitude and practice of looking after each other in the community, I think it's phenomenal in this part of the country,” he says.

What the impact of urbanisation will be on the survival of the knowledge that forms the basis of life here, remains to be seen.

“At the height of civilisation and modernisation in this country, there was a real risk that we would lose the wealth of knowledge that we have because the people who are the custodians of that knowledge are all passing away,” says Matsila.

He adds, though, they are working to retain and promote their oral history through cultural programmes and that there has been an emphasis on documenting the knowledge formally.

And, he says, people are now returning to the villages.

“Some people are beginning to say: We want our children to learn our culture. If you saw the enrolment at initiation schools, it's phenomenal… It's becoming fashionable to practice your own culture.”

Murendeni Nnzeru, at least, won't be forgetting her great-grandmother's lessons any time soon.

She has taught her the value of exercise and healthy eating, discipline and humility, she says. And does she think she will live to see her 100th birthday?

“Yes,” she says matter-of-factly.

If she's going to do it anywhere, it's here.

By subscribing to News24, you enable us to pursue stories that can help change the trajectory of our country.

Journalist: Bernadette Wicks

Images and video: Thahasello Mphatsoe

Editing: Glenn Bownes

Production and design: Mihle Mdashe